The Jewish

Community

of

La

Book Pages 15 - 22

wholesale grocer,

44 Kapellenstrasse

wholesale grocer,

44 Kapellenstrasse

Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg,

KARL NEIDLINGER

In the 19th

and 20th century, there

were two different ‘Adler’ families living in Laupheim who were not

related in any way. People used their respective addresses to

differentiate between them, even though the houses of the

‘Judenberg-Adlers’ and the ‘Kapellen Street-Adlers’ were not far apart.

The members of the former family were less wealthy weavers and livestock

dealers, whereas the latter started off as bakers and confectioners and

later on achieved considerable prosperity as wholesale grocers. Helene

Adler of the Anton-Bergmann family and grandmother of Gretel Bergmann

was a member of the Judenberg family. The Art Nouveau artist Friedrich

Adler was born on Kapellen Street.

The first chapter of

the book is dedicated to the Adlers from Kapellen Street, whose ancestor

Simon Jakob moved from Ederheim/Ries to Laupheim in the mid-18th

century. His great grandson Isidor Adler (1828-1916) founded the

flourishing wholesale business and built a prestigious residence on 44

Kapellen Street in 1876, with his shop on the first floor. Today, a café

called ‘Hermes’ can be found there (see picture below).

Isidor Adler married

twice; first, he married Judith ‘Jette’ Engel from Wallerstein/Ries in

1859 and after her death in 1874, he wed Karolina Frieda Sommer from

Buchen/Baden. Six of the nine children from both marriages reached

adulthood. At the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933, three of them were

still living in Laupheim: the eldest son, Eugen, born in 1860, as well

as two sons from his second marriage, Jakob (1875) and Edmund (1876).

Isidor Adler’s daughter Betty Wolf (born in 1863) moved back to Laupheim

from Buchen in 1939 after the death of her husband Abraham Wolf.

Before the Adlers rose to prosperity, many relatives had already immigrated

to the U.S. due to pauperism and mass poverty during the 19th

century. Only five of Isidor Adler’s eight siblings reached adulthood. Three

of them immigrated to the U.S. in the middle of the 19th century

as did his seven surviving cousins, who all emigrated between 1850 and 1863.

The company ‘Isidor Adler & Cie.’

Following the end of the war, not only the artistic works of Friedrich

Adler, but also the company of Isidor Adler fell into oblivion, leaving only

a few traces behind. Even the building on Kapellen Street, which can be seen

in the picture, was threatened by demolition in the 1980’s. No documents

linked to the company or written records of family members could be found,

neither in the Chamber of Industry and Commerce of the city of Ulm, nor in

the economic archives of the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg, where Laupheim is

situated. After the Shoah, all

traces of the forced and abrupt end of the company and the extermination of

the entire elder generation of the family were obliterated. What followed

was oblivion. This memorial book opens with this particular family, not only

because of alphabetical order, but also because of their unfortunate fate as

described above. They also played an

important role in the rise of Laupheim from a village to a city, a role in

which education was of principal significance.

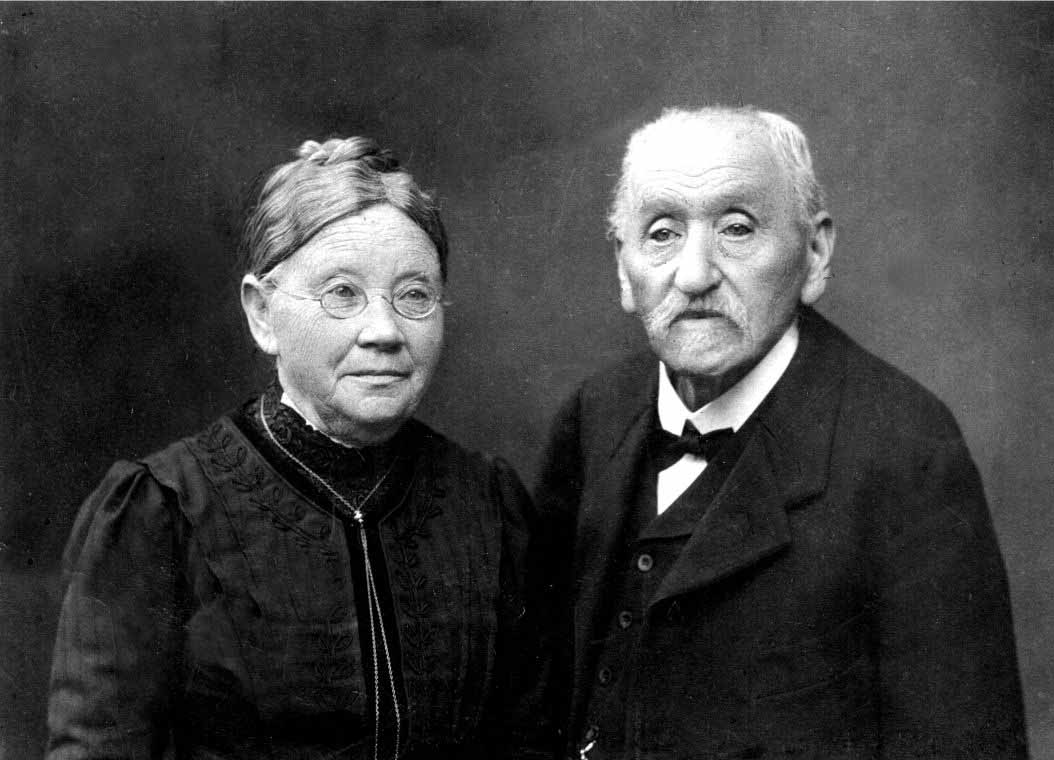

Isidor Adler and Frieda Adler at around 1912

(Taken from the archive of Ernst Schäll)

The Isidor Adler Company

gave this pewter jug to the wholesale grocer and baker Anton Schniertshauer

from Huettisheim as a gift in 1910. It bears the following inscription:

‘From the house of Isidor Adler to Mr. Anton Schniertshauer to commemorate 50 years of business relations from 1860-1910’

Only the forced aryanization of Jewish businesses in 1938/39 put a sudden

end to the business relations between the Isidor Adler Company and the

Schniertshauer grocery store (‘Fideles’). The following anecdote, which was

handed down from generation to generation and is verified by a newspaper

article, serves as proof of their excellent long lasting relations.

In 1868, the not so prosperous family of Anton Schniertshauer came to sudden

unexpected wealth when one of his sisters won the main prize in the Ulmer

Muensterbaulotterie, a lottery to

finance the restoration of the minster in the city of Ulm. But nobody in the

family dared to carry such a large sum of money from Ulm to Huettisheim, not

even Fidel. Thus, Isidor Adler had to come along all the way from Laupheim

to Ulm to fetch the 10,000 guilders, the German currency at that time.

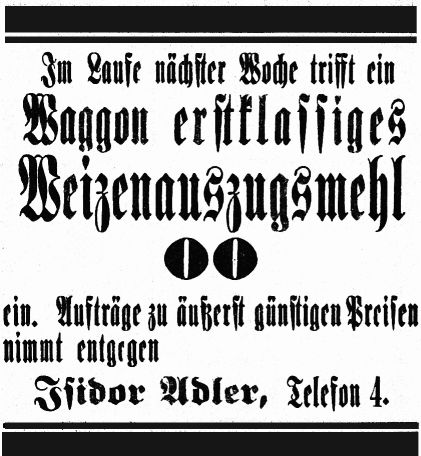

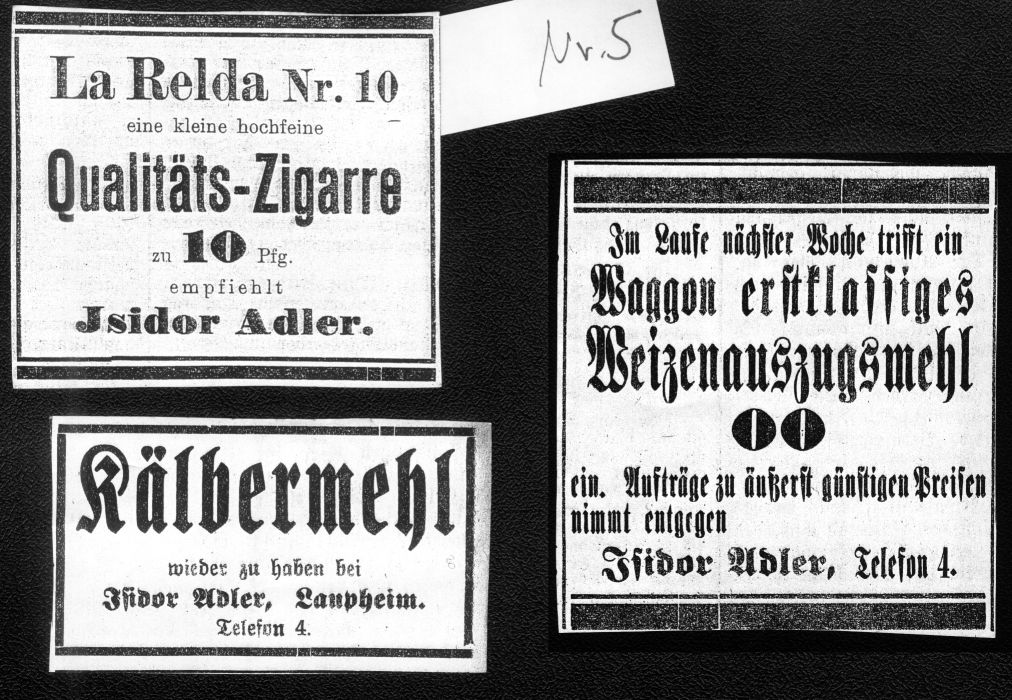

The bakers’ and confectioners’ craft marked only the beginning of the company’s history, although today not many reliable records can be found. Even Isidor Adler was trained as a baker, but managed to rise to wholesale grocer very quickly. In 1859 he married his first wife in Augsburg and one can assume that he took over the family business in Laupheim at the same time. At that time the business was located across the street next to the Steiners’ family home. Since at least the 1860’s, Isidor Adler supplied the grocery shops in the smaller villages around Laupheim with sugar, salt, coffee, wine, vinegar and oil, even adding colonial goods to his inventory later on. Soon his business relations exceeded his district. During the arrival of a large delivery, for example a whole wagon full of special flour for calves, he would sell to the consumers directly at the station.

The main office as well as the family’s residence was located in the same

building on 44 Kapellen Street, together with a wholesale food store, which

was quite spacious for that time. The other rooms on the ground floor were

used as offices, where at times not only the owners of the company, but also

up to three employees used to work. Behind the building, storerooms,

stables, garages, a coffee roaster and a wine bottler could be found.

Warehouse workers, coachmen and drivers worked there, so that in times of

prosperity as many as ten people were employed by the company. This still

did not include the maids working in the household, of which Isidor Adler’s

family always had three. Even before World War I the company bought their

first truck to serve their customers in a better and faster way. The

family’s telephone number was ‘4’, which shows that they were not shy about

investing in new technologies.

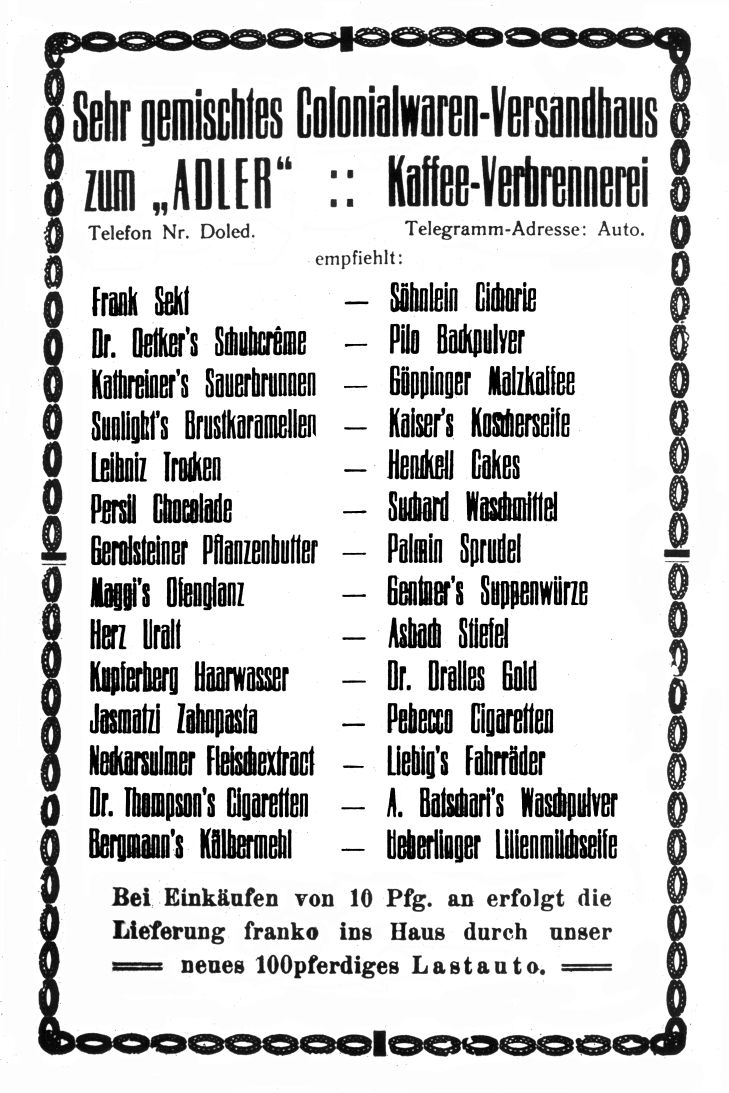

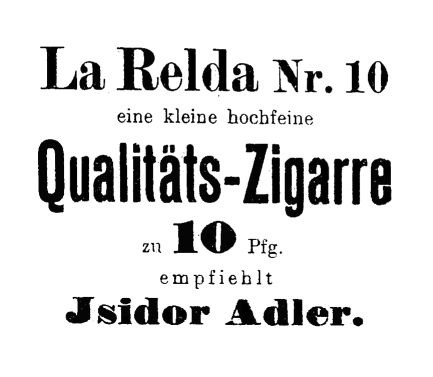

For Purim, the Gesangsverein

(choir) ‘Frohsinn’ organized at

least one ball per year, a social event with an extensive program, sometimes

even including a printed pamphlet with all kinds of funny commentaries. An

advert by the Isidor Adler Company can be found in one of those pamphlets

from 1912 on page 20 on the left side, giving a good impression of the wide

variety of products sold by the company: the days of the confectionery had

long been left behind. Although the unknown authors of the adverts changed

over time, it is remarkable to see that about half of the brands mentioned

in these pamphlets can still be purchased a hundred years later. The other

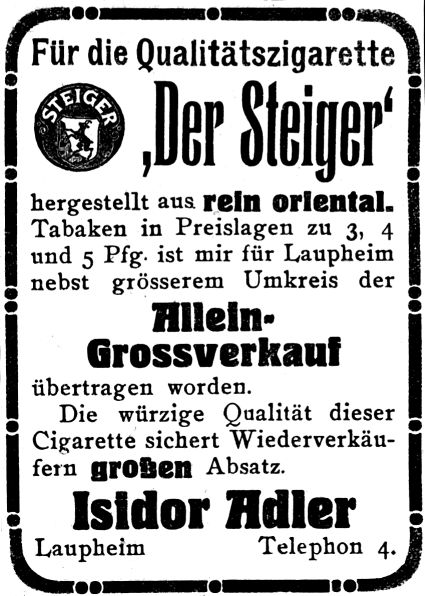

adverts (see below and on the following pages) were all taken from

Laupheim’s former local paper, ‘Laupheimer

Verkuendiger’. Such adverts are nearly the only traces left today that

provide information about the Isidor Adler Company.

Hardly anything is known about the economic impact the Nazi era had on the

Isidor Adler Company except that the former authorized signatory, Gebhard

Schneider, took over in 1939 and ran the company under his name. The same

can be said about the post-war situation, because, unlike as was the case

with other families and companies, there are no documents concerning

negotiations of restitution and compensation in the National Archive of the

city of Sigmaringen. All the remaining information from the time of the Nazi

era deals mainly with family matters and will be displayed in the following

paragraphs.

A scaled down advert

taken from the local paper ‘Laupheimer Verkuendiger’ is supposed to tell the

customers: Times are bad. Stock up now! The outbreak of World War I seven

months earlier led to the ‘lack of raw materials’ mentioned in the advert

and made further deliveries of special flour for calves impossible. The

advert from March 13, 1915 shows clearly how quickly Germany was running out

of raw materials and food due to the war.

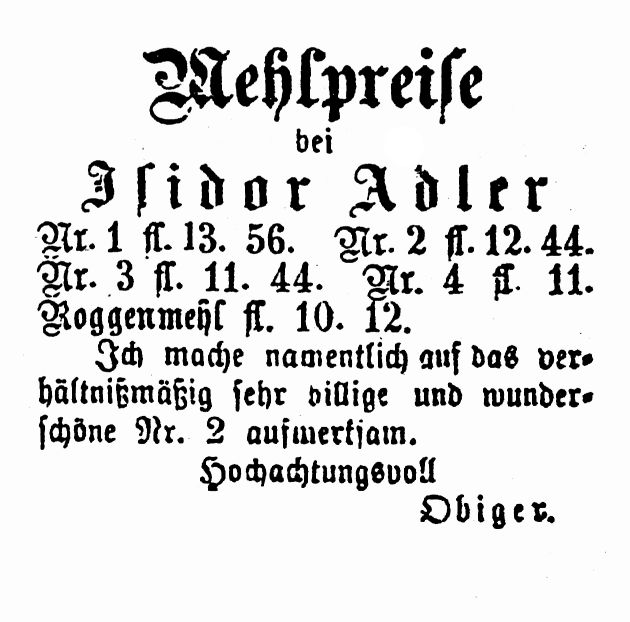

The oldest of the adverts

down below dates back to January 31, 1874. In the ‘Laupheimer Verkuendiger’,

Isidor Adler advertises his flour prices and recommends flour No. 2. At that

time, guilders and kreutzer were still the common currency in Germany (fl =

guilder, one guilder consisted of 60 kreutzer). The changeover to the new

national currency, the Reichsmark, took place a few years after the

foundation of the German Reich in 1871. The Reichsmark was introduced in the

state of Wuerttemberg on July 1, 1875. One guilder was 1.75

Reichsmark.

|

|

|

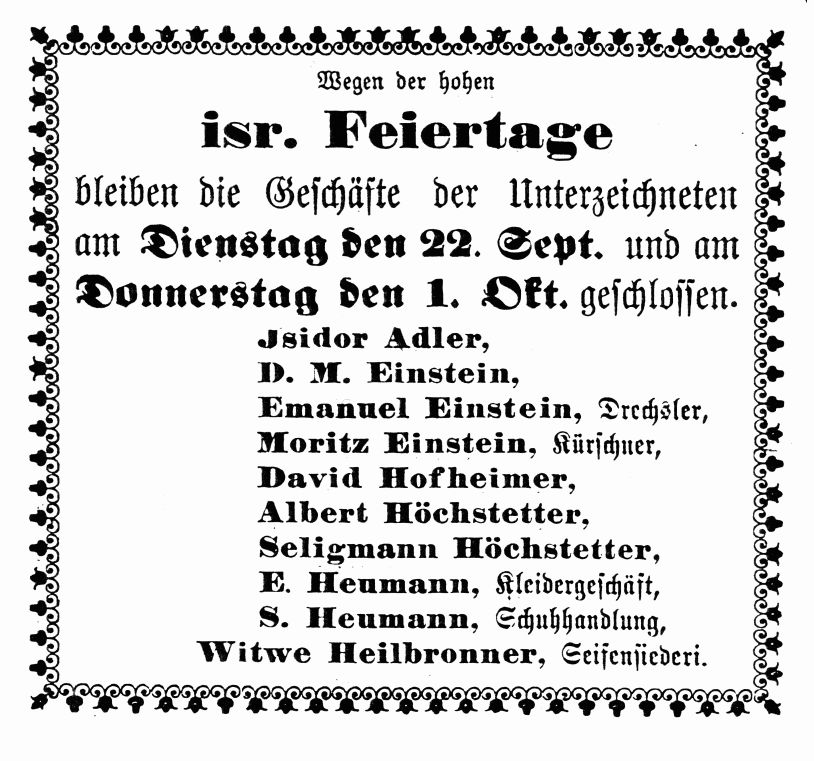

The ‘high holidays’ in

autumn start with the traditional Jewish new year festivities of Rosh

Hashanah, which fall on a different date each year. Rosh Hashanah is then

followed by the most important Jewish holiday, Yom Kippur; after that,

Sukkoth is celebrated. The high holidays come to an end with the celebration

of Simchat Torah. Should New Year and Yom Kippur fall on a workday, Jewish

shops would remain closed, as was the case in 1903 and 1924.

Some of the companies who

had put their adverts in the ‘Laupheimer Verkuendiger’ in 1903 did not exist

anymore in 1924, such as a tailor’s shop called Hoechstetter, or Einstein, a

turner’s workshop. Other companies chose not to close their shops on the

special holidays mentioned above.