NÖRDLINGER,

Benno,

NÖRDLINGER,

Benno,

The Jewish

Community

of

La

Book Pages 384 - 390

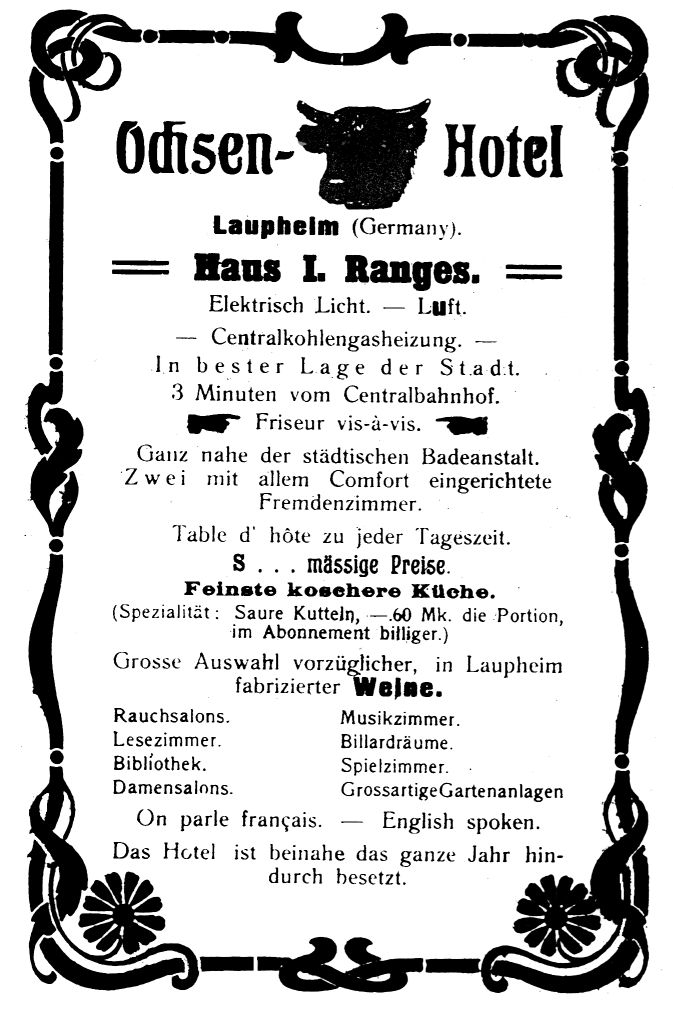

Inn "Zum Ochsen", 23 Kapellenstrasse , 4 Radstrasse

Inn "Zum Ochsen", 23 Kapellenstrasse , 4 Radstrasse

KARL NEIDLINGER

Benno Nördlinger, born November 14, 1895 in Laupheim, died 1979 in New York,

Sophie Nördlinger, née Sänger, born April 3, 1898 in Laupheim, died 1993 in Chicago. Sophie Nördlinger’s mother:

Klara Sänger, née Einstein, born April 8, 1865 in Laupheim, died October 15, 1942 in New York.

July 1938, Nördlinger-Sänger family on the stairs of the “Ochsen” with guests. From left to right: unknown couple, Klara Sänger, Sophie Nördlinger, Sam Simon, Benno Nördlinger. Boy in front: Nephew Fritz Bernheim. (Archives of Ernst Schäll)

As you would expect of a well-established, innkeeper family, there are many

pleasant photos of the Sängers and Nördlingers, mostly thanks to Ernst Schäll’s

Archives. Registered records are,

however, in shorter supply. The texts about

this family are rather short and leave many questions unanswered.

„Zum

Ochsen“

Sophie Sänger was the only child of Albert and Klara Sänger. The Sängers

took over the traditional German inn

Zum Ochsen from Albert’s father, Benjamin Sänger, who had purchased the

inn in 1860. The house had already been built around the turn of the 18th

century. The word Rot (red) was

probably added to the original name in the 1980s, after the building had

fallen into disrepair and was under threat of demolition. Following

restoration in accordance with the guidelines for the protection of

historical monuments, it was reopened under the name

Zum roten Ochsen.

In the advertisement of the Purim

magazine of 1914 it is only called

Ochsen Hotel. The advertisement makes ironic jokes about the small size

and the old-fashioned and somewhat backward style of the inn at the time, as

there were already many bigger and better inns in town. Furthermore, we

learn that tripe is a specialty and a true kosher staple.

Playful advertisement from the musical society

“Frohsinn” in the “Purim” magazine of 1914.

At Purim Fair every year anonymous authors would poke fun

at what was going on in town.

(Source: property of John Bergmann, city archives Laupheim)

The innkeepers of Zum Ochsen:

Klara and Albert Sänger with their daughter Sophie (middle)

and two unknown children in 1914/15. Albert Sänger died in 1929.

(Archives of Ernst Schäll)

In John Bergmann’s recollections the beloved meeting place

Zum Ochsen never lost its

popularity despite increasing competition. He describes the situation during

the 1920s as follows:

People spent a lot of time in the Ochsen, one of the two Jewish-German inns. The Ochsen was a place for open discussion where Jewish people could meet, play cards and talk. Men usually met there after lunch on their way back to work for a cup of coffee (without sugar and milk, since the Ochsen strictly adhered to Kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws). During this time they also played card games such as Poker and Gaigel or read Tarot cards, but there was also room for insightful discussion on local and international issues.

(Bergmann chronicles, Page 59, 63)

Benno Nördlinger

The last Jewish innkeeper of the

Ochsen was Benno, whose parent’s home was located nine houses up

Kapellenstraße on the same side of the road as the inn. Benno was

the oldest son of the farmer Ludwig Nördlinger and his wife Pauline

(Page

394 ff.). From 1905 to 1911 he attended Laupheim

Realschule (the German equivalent of High School) and graduated with

Mittlere Reife (a high school

diploma), known as Einjähriges at

that time. On finishing his

Einjähriges, he began his commercial apprenticeship, shortly before the

outbreak of World War I. At the age of nineteen, even Benno was swept up in

the patriotic enthusiasm for war. In the autumn of 1914 he volunteered to

fight in the war, as did 13 younger members of the Jewish community of

Laupheim. During the war he fought as an artilleryman on the frontline, was

promoted to corporal and was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd class.

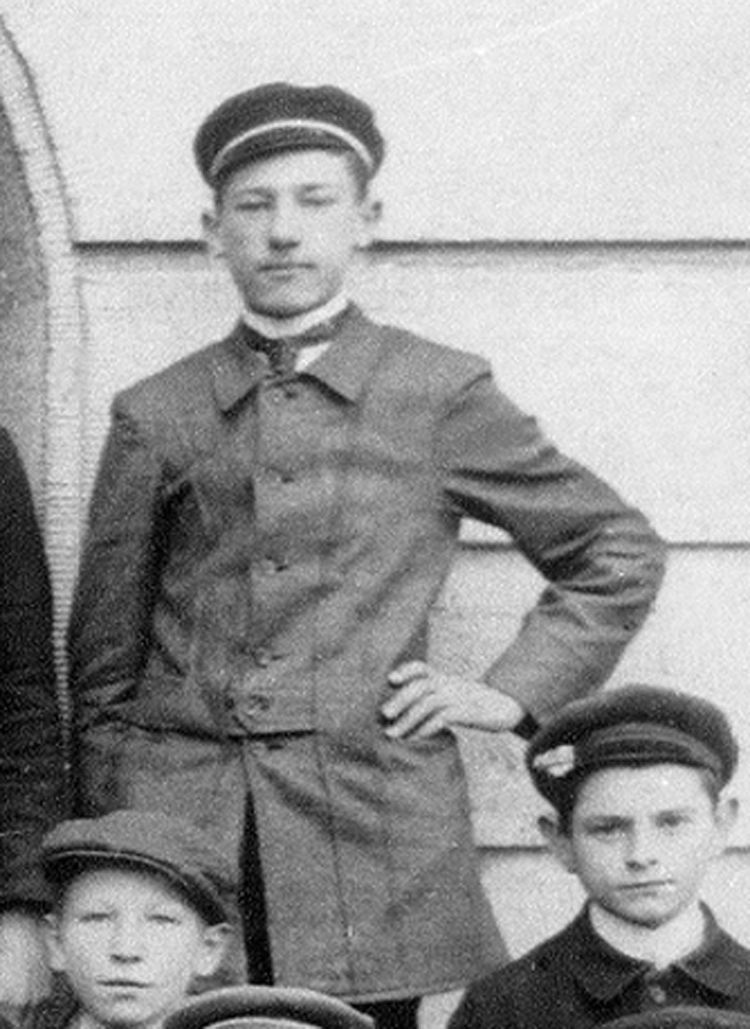

Benno Nördlinger as a schoolboy in 1911.

(Archives of Ernst Schäll)

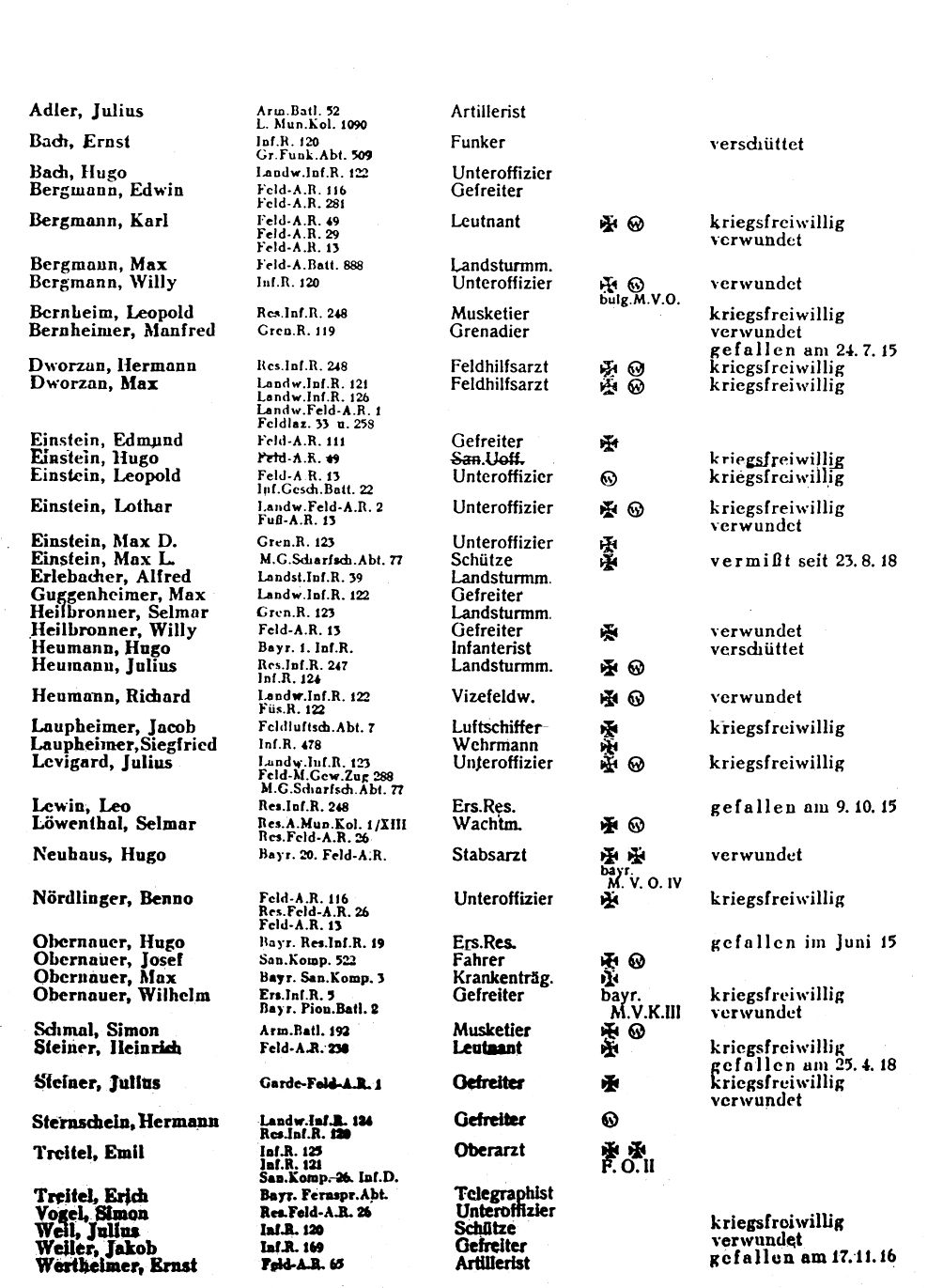

The list of Laupheim’s 45 Jewish frontline soldiers, which is shown below,

was found on the property of John Bergmann, but unfortunately no sources are

provided. This list is surely a product of the so-called “Jewish census”

that was conducted by the Imperial Army in 1917 exclusively for statistical

purposes. This later served as part of the anti-Semitic campaign after the

war, the purpose of which was to downplay the patriotic contributions of the

German Jews. Looking closely, the number of Laupheim frontline soldiers is

striking. Most of the soldiers behind the frontline were older and are not

even listed here. This shows that Benno Nördlinger was not an isolated case.

Half of the soldiers, namely 23, were awarded an Iron Cross. Moreover, 14,

almost a third, were promoted: 10 to the rank of corporal and 4 to the rank

of officer. As promotion was usually only possible with a certain level of

education, i.e. Einjähriges, this further demonstrates that the Jewish community had

a better than average level of education.

It is estimated that Benno Nördlinger and Sophie Sänger married in early

1926. Benno became the new innkeeper of the

Ochsen. The couple, which would

remain childless, rented a house on Radstraße several houses up from the

“Ochsen”. This was due in part to the spatial constraints of the

Ochsen that are still obvious

today. Another reason for this may be the fact that Paula Seligmann, the

widowed sister of Klara Sänger, lived there temporarily. Paula Seligmann

died in 1939 in Stuttgart, but she was buried in Laupheim in the cemetery.

The “Ochsen” before World War I

In the 1920s Benno Nördlinger ran a paper wholesale business together with Hugo Höchstetter, however, the information available is limited. At the time Benno’s in-laws probably still ran the inn, therefore the paper wholesale business was likely to have been the main source of income for the Nördlinger family.

Jewish frontline soldiers

Name,

field unit,

last rank,

decorations,

honorable

mention

Emigration and new beginnings during the Third Reich

Due to a lack of authentic reports this chapter is rather short and limited

to key figures. John Bergmann describes how the

Ochsen became the target of SA

terror early on. After the failure of the coup d’état in Austria in July

1934 numerous members of the SA and the SS were taken in by Germany, among

others by the Steiger-Werke, a car

factory, in Burgrieden. From there they often came to Laupheim:

“What our local Nazi-units were lacking in brutality and malice, they learned quickly from their Austrian comrades. The officers were welcome guests at the homes of the ‘better families’. In 1934 these gangsters were already raging against Jews. They temporarily occupied the Ochsen inn and damaged many Jewish houses and shops.” (Bergmann-Chronicles p.85)

In 1938 during the Night of Broken Glass Benno Nördlinger was also dragged

out of his home, humiliated and subsequently deported to the concentration

camp Dachau. In a letter dated November 23, 1938 his lawyer, Ernst Moos from

Ulm, tried to negotiate with the Gestapo for a swift release.

He argued that the already initiated sale of the

Ochsen to the castle brewery could

not be finalized as long as Nördlinger was arrested. The emigration of the

family had already been prepared and the visas for the U.S.A. were about to

be issued. He also enumerated the prisoner’s decorations and honorable

mentions: almost four years of military service at the frontline, Iron Cross

2nd class, the Honor Cross of the First World War for front-line

veterans and many years of service in the medical orderly convoy.

(Source: property of John Bergmann, Reel 1, Box 2)

On December 14, 1938 Nördlinger was finally released. In the end, the sale

of the inn to the castle brewery was not officially authorized; instead it

was sold privately in February 1939. Shortly before the outbreak of World

War II, on August 14, 1939, the family was finally allowed to immigrate to

New York. Even Klara Sänger who was 74 years old at the time accompanied

them. This was probably a wise decision that saved her from humiliation and

deportation. Others at her age commonly did not have the fortitude to

undertake such a long journey. She died in New York in October 1942.

Even though they had lost everything, Sophie and Benno Nördlinger were able

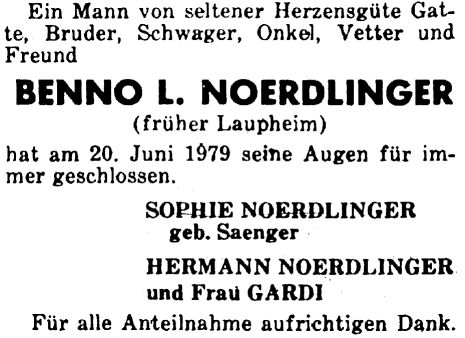

to build a new life for themselves in New York. In June 1979 Benno died at

the age of 84, as documented in his obituary notice that was published in

the newspaper Aufbau

(Reconstruction). His wife Sophie outlived him by many years. In November

1993 she died at the age of 96 in Chicago, in a home for the elderly. She

had lived in Chicago since 1990 to be closer to her nephew, the architect,

Fred Bernheim.

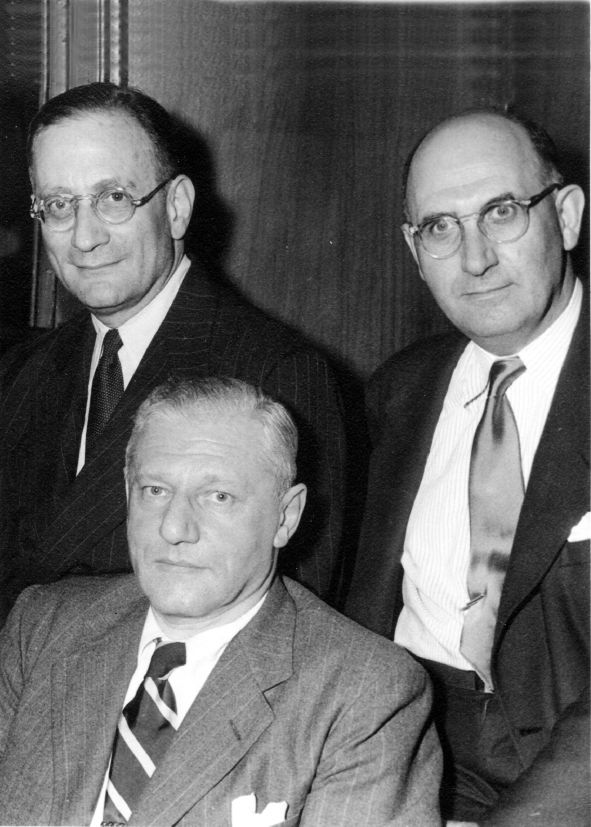

(A photo from 1950: back row: Julius and Helmut

Steiner,

In front: Benno Nördlinger - The “Grandseigneurs”

(sophisticated gentlemen)

of the destroyed Jewish community of Laupheim)

Sources:

Property of John Bergmann, City archives Laupheim,

Köhlerschmidt/Hecht: Die Deportation der Juden aus

Laupheim (“The deportation of the Laupheim Jews”)

John H. Bergmann: Die Bergmanns aus Laupheim

(“The Bergmann family from Laupheim”)